Developmental toxicity (DevTox) occurs when a chemical or substance disrupts an organism’s normal growth and developmental processes. The mechanisms underlying developmental toxicity may include structural malformations, molecular growth pathway interference, or impaired cellular differentiation. A substance’s toxicity is typically assessed by the degree of disruption in these developmental pathways and the severity of the resulting health effects1.

To limit public exposure to hazardous substances, proper safety testing of manufactured chemicals is critical. Regulatory agencies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the United States and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) internationally play a crucial role in setting testing guidelines and defining toxicity parameters, including the requirement for DevTox testing for regulatory approval2. These agencies monitor adverse health outcomes associated with consumer chemicals during their launch and post-marketing, and place restrictions on the intended use of chemicals as needed. Therefore, it is in the best interest of manufacturers to proactively conduct extensive toxicity testing and establish safe dosage ranges before investing significant time and resources into product development.

Conventionally, mammalian models are used to predict human responses because of shared physiology and similar biological pathways. Testing on mammalian models—such as rats, mini pigs, dogs, and monkeys—is costly, labor-intensive, and raises ethical concerns. In fact, the FDA recently announced an initiative to phase out animal testing in favor of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). To ethically and cost-effectively assess the safety of the thousands of manufactured chemicals requiring evaluation, a robust and reliable alternative model for toxicity testing is needed.

C. elegans as a Model Organism for Developmental Toxicity (DevTox) Testing

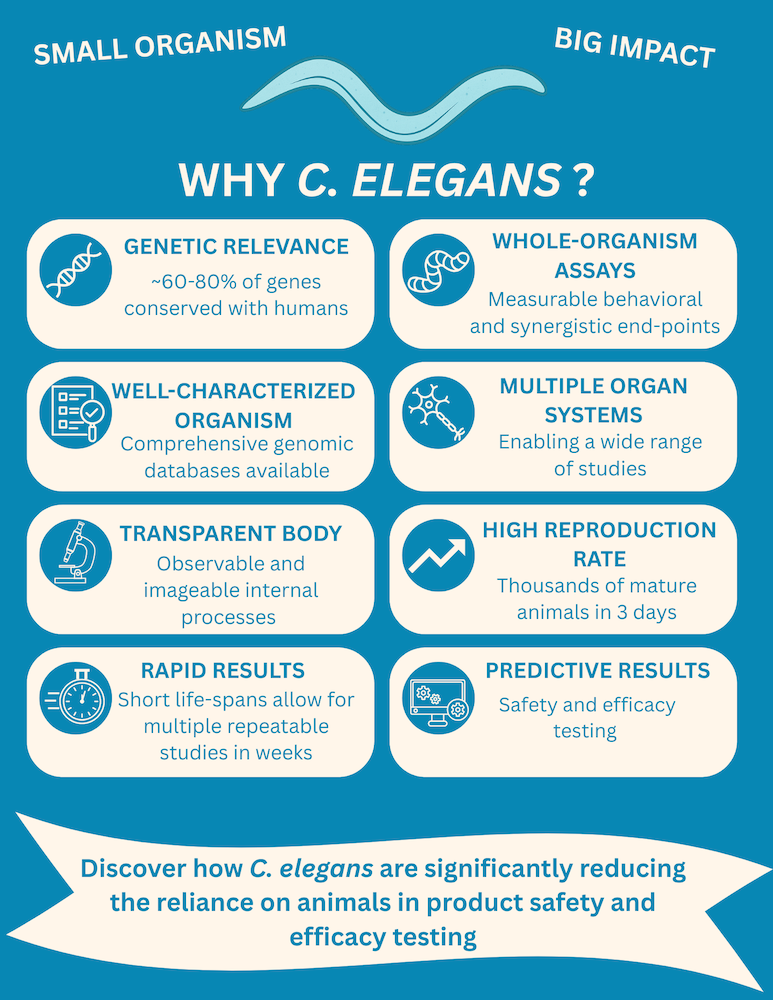

Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), a species of nematode, has emerged as a powerful model in predictive toxicology. Its short lifespan, high reproductive rate, and small size make it an easy and cost-effective organism to use in scientific experiments. Since its debut in laboratory research, C. elegans has been extensively characterized: its entire genome has been sequenced, its entire nervous system and connectome has been mapped, its development and cell lineage are understood down to the level of individual cells, and many of its genes and signaling pathways have been identified—approximately 60-80% of which share homology with humans. Additionally, C. elegans possesses multiple organ systems, an active metabolism, an intact reproductive system, a connectome with all the major neurotransmitters, and a transparent cuticle — enabling real-time observation of fluorescent markers and internal processes3-5. With widely available genetic tools (CRISPR/Cas-9 and whole-genome RNAi library) and strain resources (fluorescently labeled worms, >2000 mutants, and more than 1000 wild isolates), C. elegans is being used for a mechanistic understanding of key toxicology pathways. These features make C. elegans particularly valuable for DevTox studies.

Studies have demonstrated that C. elegans can predict mammalian developmental toxicity with approximately 89% accuracy6. Large-scale DevTox studies have demonstrated similar concordance with rat and rabbit data, while using a gross developmental parameter in C. elegans with a flow cytometer-based technology7, known to have high variability8. With advancements in microfluidic technology and integration with AI/ML platforms, we can now achieve high-content analysis of multiple parameters with high statistical power. By following robust, standardized protocols and maintaining proper culturing practices, vivoVerse researchers can obtain reproducible and reliable results across well-defined toxicological endpoints using C. elegans9.

vivoVerse Developmental Toxicity (DevTox) Assay

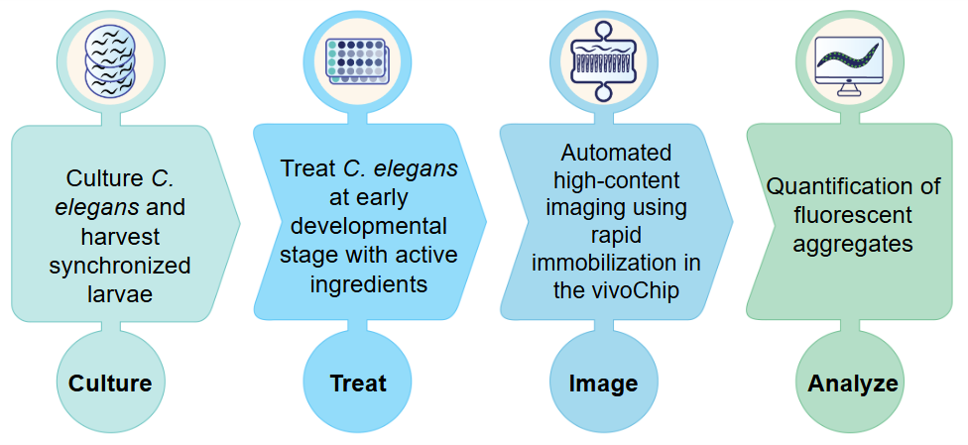

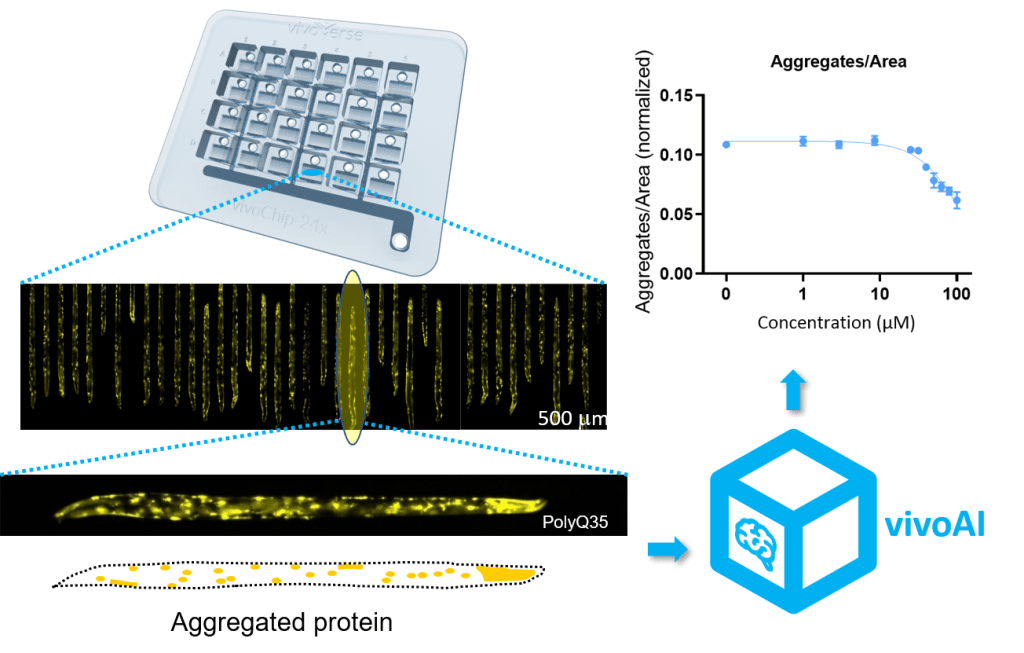

To support the growing needs of the industry, vivoVerse has developed the fully automated DevTox Assay using C. elegans. This assay evaluates chemical toxicity by analyzing key developmental endpoints in adult C. elegans after chronic exposure to chemicals. Age-synchronized worms are exposed to a reference chemical from their L1 developmental stage for 72 hours until adulthood. Treated worms are loaded into a vivoChip-24x, a microfluidic device that immobilizes ~1,000 worms across 24 distinct populations, and high-resolution images are taken of each worm. The worm length, body area, and volume are then calculated and analyzed by vivoVerse’s machine-learning (ML) powered image-analysis pipeline9.

The microchannels in the vivoChip-24x devices are designed to capture the entire worm body in a single field of view, allowing for precise measurement. Two variants of the device support worms of different sizes, making it particularly useful in DevTox studies, where toxicity may significantly affect worm size and growth.

Figure 1: An automated developmental toxicity (DevTox) testing using C. elegans.

Scalable, Automated DevTox Data Collection

For each chemical tested, we analyze up to 1,400 C. elegans from 12 unique populations, including two assay controls (vehicle and positive controls), and three biological replicates using the vivoChip. This setup enables the collection of repeatable DevTox data across 10 concentrations and estimates effective concentrations (EC10) with high statistical power. Manual analysis of such large quantities of data is incredibly time-consuming. vivoVerse’s ML-based model segments ~1,000 individual C. elegans bodies from one vivoChip in just 10 minutes and automatically calculates three developmental endpoints: worm length, body area, and volume, analogous to key mammalian metrics. The precise ML analysis captures small variations between samples, enabling statistically powerful data with very low variability (coefficient of variance, CV <8%). The data analysis automation greatly reduces time spent analyzing data, mitigates human error and inconsistencies, and eliminates bias.

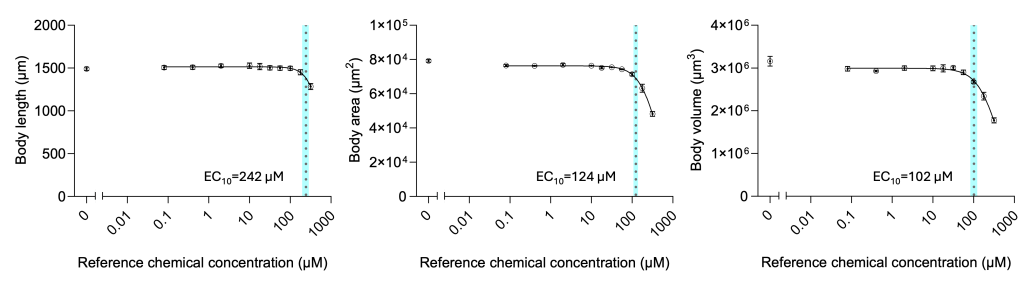

Case Study: Developmental Toxicity of a Reference Chemical

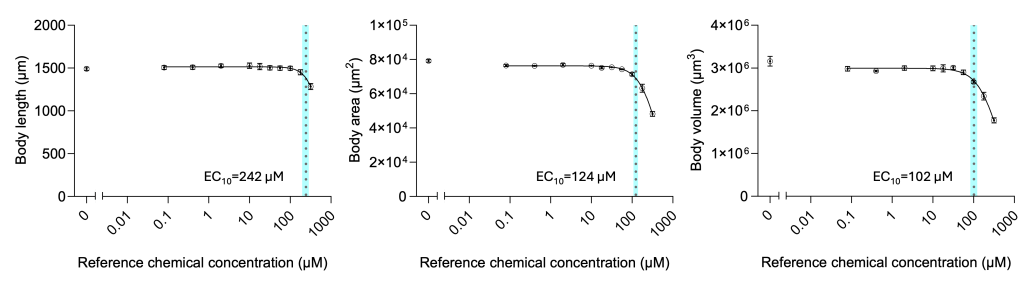

Using the vivoVerse platform, we tested several reference chemicals across various industries, including agrichemicals, industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and food ingredients. Here, we present the results of a case study from one of the reference chemicals. First, we performed the range-finding assay with the reference chemical and identified the lethal concentration (LD50 = 105 µM). We then characterized three sub-lethal parameters using 10 concentrations below the lethal concentrations. All three sub-lethal DevTox parameters are shown in Figure 2. Among the three parameters, we found the volume to be most sensitive.

Figure 2: Multiple body parameters for concentration-dependent DevTox analysis with one reference chemical. C. elegans were exposed to ten concentrations of a reference chemical and 1% DMSO in the liquid culture. Concentration curves for body length (A), body area (B), and body volume (C) were collected and analyzed using the vivoVerse DevTox Assay and AI model. The data from 3 biological replicates are denoted as mean ± SEM. The vertical dotted lines represent the effective concentration (EC10) values, representing a 10% change in the parameter, are determined by fitting the dataset to a 4-parameter, variable slope Hill function.

Summary:

The highly sensitive, accurate, and reproducible vivoVerse DevTox service, which includes range-finding to identify lethal and maximum sub-lethal concentrations in C. elegans, leverages the vivoChip-24x microfluidic device in conjunction with an ML model to deliver a rapid, high-throughput method for (1) screening active ingredients for toxicity, (2) prioritizing chemical leads, and (3) contributing to read-across strategies. Our services can help our customers reduce reliance on animal use while protecting the environment and promoting public health. As regulatory agencies continue to shift toward non-animal testing models, tools like the vivoVerse’s DevTox assay are poised to become a cornerstone in the future of ethical, efficient, and scalable chemical safety evaluation.

Sources

- Rangika S. H. K. & Perera, N. Toxicity testing, developmental. Encyclopedia of toxicology, Academic Press, Editor Wexler, P. Pages 349-366 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-824315-2.01051-4

- Test No. 421: Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals. (OECD, 2016).

- Riddle D.L., et al., editors. C. elegans II. 2nd edition. Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. Section I, The Biological Model. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20086/

- Kaletta, T. & Hengartner, M. Finding function in novel targets: C. elegans as a model organism. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5, 387–399 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2031.

- Hunt PR. The C. elegans model in toxicity testing. J Appl Toxicol. 2017 Jan;37(1):50-59. doi: 10.1002/jat.3357

- Harlow, P., et al.The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a tool to predict chemical activity on mammalian development and identify mechanisms influencing toxicological outcome. Sci Rep 6, 22965 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22965

- Boyd W.A., et al. Developmental effects of the ToxCast™ Phase I and Phase II chemicals in Caenorhabditis elegans and corresponding responses in zebrafish, rats, and rabbits. Environ Health Perspect. May;124(5):586-93 (2016). https://doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409645. Epub 2015 Oct 23.

- Moore B.T., Jordan J.M., & Baugh L.R. WormSizer: High-throughput analysis of nematode size and shape. PLoS ONE 8(2): e57142 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057142

- DuPlissis A., et al. Machine learning-based analysis of microfluidic device immobilized C. elegans for automated developmental toxicity testing. Sci. Rep. 2025 Jan 2;15(1):15. https://doi:0.1038/s41598-024-84842-x.